Below is an article I wrote in 2006 for a hunters’ publication. It tells the story of a sheep hunt I went on as my Dad’s sidekick. The end of that trip was my first time to Seattle. Now that I am summering here with my kids, I can’t help but remember it. Since then, I’ve married and had children, and I’m no longer accompanying Dad on his hunting excursions. I’m grateful to have had occasion to write it down; it’s so fun to look back on.

“This is my third go at Stone sheep out at Scoop Lake,” one man said to the other across the aisle of our Air Canadian flight to Whitehorse, Yukon. Eavesdropping, my father and I gave each other a momentary look of unease, a look we’d grow increasingly familiar with over the next two weeks. I could see the words ‘third go’ mixed with certain expletives written in my father’s face.

The Stone sheep season began in only a few days’ time, and residents and nonresidents alike would scatter across the Canadian wild for a chance at its game. We, along with most our flight, were on our way to such a sheep hunt. I was not so sure, however, that we, as most our flight, qualified as “sheep hunters.” It is true that my father and I are both hunters, and have been all our lives. I am told that at the age of four when the scent of warm, freshly slain Whitetail poured out of the deer’s open body I exclaimed, “Ah! The smells of Christmas!” Most definitely, we are hunters. It is also true that my father took his Dall sheep on a rigorous Alaskan hunt in 1991. But looking around the plane, I decided much to my alarm that despite these truths, we were not sheep hunters.

“Sheep hunters” wore flannel over hard, muscular physiques. Their thick ankles grew boots that seemed chiseled from tree bark and expertly weathered by hell. Their dense facial hair fell within the shade of greasy baseball caps affixed with logos of farm equipment or gun manufacturers. They closely resembled the hardworking, rough-riding characters I had seen only on Marlboro billboards and my Brawny paper towel packaging. Dad and I, at ages sixty and twenty-five respectively, did not seem to fit neatly into this crowd.

My father had booked our ten-day Stone sheep hunt through Scoop Lake Outfitters. He planned to pull the trigger while I, official gun bearer, would ensure that he and his rifle were at the top of the mountain with a shot to do so. The plan was to hunt a piece of Scoop Lake’s 4,000 square mile expanse of Northern Rockies in British Columbia. Scoop Lake’s reputation for Stone sheep was the topic by rote at safari clubs and hunting expos throughout the world. A North American legend, its reputation had even survived more recent rumors and publications that its sheep were tapped out and its numbers dwindling. Dazzled by the prospect of such adventure, Dad and I had basked in the misery-to-come in the way we always anticipated these big trips—intense euphoric expectation that would not fully be replaced by fear until Mom dropped us off at the airport. When we found ourselves one flight and two airports removed from Mom, that fear had mounted to a breath-catching, copper-tasting secretion in my throat.

At one of two baggage carousels at the Whitehorse airport the passengers gathered, anxiously shifting weight from one foot to the other like nervous game at a watering hole. But as gun case after silver gun case spewed from the chute’s belly and bumped noisily along the carousel track, tensions eased and introductory conversations began. Outfitters’ names were dropped, rifle calibers exchanged, and trophy expectations aired. It was at this point that Dad and I met Tom and his adult son, each of whom (like my father) booked Stone sheep hunts with Scoop Lake. Tom was good looking, charismatic, and my father’s age, but any friendship that might have blossomed between them died stillborn the minute Tom declared there was no mountain height he could not climb to reach his sheep. Tom gave the weight of this statement little time to digest before he produced the photo album evidencing his last Stone sheep— an impressive 42” trophy— that Tom returned this year to trump. Enduring Tom’s confidence in the face of my own fear felt a bit like eating a plate of cold, day-old eggs. Every minute we waited for that taxi sent us deeper into Tom’s musings on his sheep hunt, which were mostly of how he created the mountain-climbing, horseback-riding stealth machine that stood before us. He and his son spent a great deal of time training and researching this very expedition, and already knew which campsite, which guide, and even which mountains they paid to hunt. Staffed with much less information, Dad and I exchanged our second look of the day, and the fear became a frantic, kinetic tribal dance of grotesque pygmies in my gut.

The journey from Whitehorse to Scoop Lake is no small feat. Our arrangements, shared by the other Scoop Lake hunters, included an overnight in Whitehorse, a four-hour car ride to Watson Lake, a floatplane ride from Watson Lake to Scoop Lake headquarters, and lastly a floatplane ride from Scoop Lake to one’s assigned hunting camp. Despite these hurdles, Scoop Lake’s impressive reputation for Stone sheep rose as the seductive sirens’ song; it held the hunters in eager anticipation of the adventures that lay ahead, time and expense be damned. And, if reputation alone did not suffice, Scoop Lake’s rich history offered any historian a warm embrace to counter the strains of arrival. My father was one such hunter.

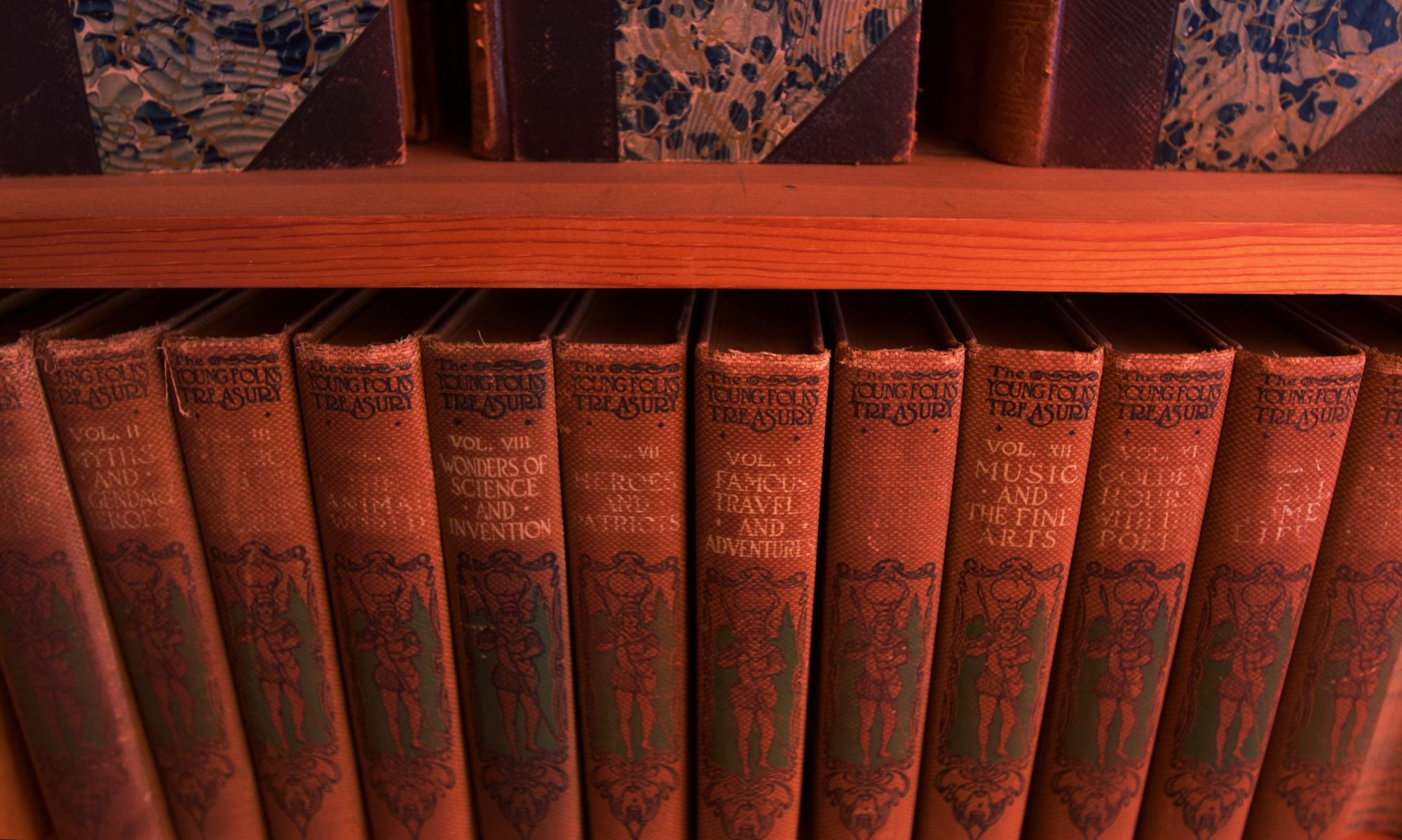

When Frank Cooke bought the land west of Kechika River from Skook Davidson for $5,000 in the early 1960s, he scored a reputable and untapped natural resource. With a mind to guide the area, he recalled in interviews that the land overflowed in sheep, moose, caribou, and goat. Above a basin between the Turnagain and Colt Lake, Cooke recalled counting as many as sixty-seven rams in one herd, a figure he attributed to the land’s successful wolf-control programs and lack of hunting. Undoubtedly, my father (thanks to the knowledge derived of books such as these) counted out sixty-seven rams instead of simple sheep each night when head met pillow and eyes closed tightly to dream.

My entire life, Dad has graced each trip with its own reading list, tailored specifically to regions and activities so that wherever we were—diving the Great Barrier or on African safari— we might experience it while reading of deep sea shark attacks or lions who hunt in darkness. In our family, a trip is truly great only on the other side of perfectly paired book selections to complement the travel. For this sheep hunt, despite the fact that our floatplanes grimaced at take-off with every pound of weight, Dad’s library lacked nothing. Brought to fan the flames of fantasy and adventure on our trip, it included accounts of the Klondike, biographies of Frank Cooke, poems by Robert Service, stories by Jack London, Pat McManus’ humor, and countless mountain climbing tales, mostly of Everest. I dare say that despite the days spent in tiring travel, we arrived at Colt Lake (our assigned hunting camp) as though shot from the slingshot of boyish hope and expectation. Then we looked around.

I had scarcely noticed where it was they left us for all the distraction of plane noise, struggles with luggage, and the fierce handshakes of our hunting guide and horse wrangler. But as the sounds of our Beaver faded around the mountain I became acutely aware that with it went the world and before me lay a dispiriting sight: 350 degrees or more of desolate mountain, valley, and lake, and then a sliver of habitation—a wooden plank leading to a 15-foot shack, a horse corral, a shed, and an outhouse. Before me lay the famous and historic Colt Lake camp.

The shack housed our kitchen and sleeping quarters. Once inside I was told to pick a bunk, and then if hungry, to make a plate. The back of the cabin partitioned from the kitchen and dining area held four bunks, two up and two below. Each bunk owned its own mattress of yellow foam turned brown with age and splotched with mysterious and not so mysterious stains. A standing shower in one corner was immediately promising, but I discovered its floor was used for storage and its shower bag was shriveled from disuse. Half naked women mocked me from the cardboard walls on which they were tacked. I arranged my sleeping bag so as to touch the foam as minimally as possible, particularly the precarious three-inch wooden border where dirt and human discard reminded me just how historic Colt Lake truly was. At this, I decided to inventory lunch.

Two steps later I had joined them at our buffet, which I studied with a feigned air of satisfaction. A loaf of mystery meat, recently sliced, sat with its congealed outer layer of brackish jelly that still bore the imprint of the can that birthed it. There was a sandwich spread of mayonnaise dotted with green and red flecks, white bread, and Tang to wash it down. Over lunch our hunting guide and wrangler discussed the persistent mice problem. I lost a few words over the white noise of the hand-held trucker’s radio connecting us to others, but I caught more of the conversation than I would have liked. In my sleeping bag that night with the radio’s ccrr ccccrrrr to set the mood, I conversed with my nerves on waking early, riding horseback and climbing mountains.

The next afternoon, our horse wrangler sat clutching a broken arm waiting for his medical evacuation by floatplane. This injury, sustained at the wild temperament of his horse, catapulted the conversations with myself to screaming fits inside my head. In all my naivety, I pictured the horse wrangler to be the horse whisperer—the one who would guide the reigns of my steed as we negotiated difficult terrain. As I watched him disappear around the mountain only one day after my arrival, my heart sank. A calm, simple, ageless hunting guide by the name of Bob bore complete responsibility for us now.

Bob played by the book. Unfortunately, the book demanded that we, as guided hunters, abide by stricter standards than resident hunters. Our ram must not only be a legal sheep by way of trophy size, but it must be aged at eight years. Aging Stone sheep requires close enough proximity to count the rings on the horns. This closeness proved to be as elusive as the Bongo, and as mysterious.

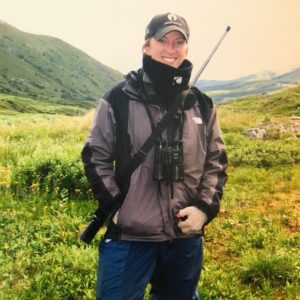

I came to learn that the sheep hunt is a game of patience unlike rattling Whitetail or hunting from blinds. It sucks the very marrow from the hunter’s bones. To sheep hunt means to rise early, mount up, and ascend mountains on horseback in cold rain. This might take an hour or three before you dismount and continue climbing on foot. Several hundred feet in elevation later, the hunter sits and “glasses,” which means to scan the mountainsides using binocular and spotting scope. It is difficult for the untrained eye to find anything in the crags and rocks. After hours, and now soaked through to skin, the guide may find Stone sheep. At this, the hunter’s heart flutters and subsides as he endures perhaps another hour in the evaluation of the Stone sheep, most likely spotted on a mountain ledge a thousand yards away. The curl of the horn is determined ‘legal’ or ‘not legal’. It is at this juncture that the guide and hunter discuss the best way to get closer to the sheep. The hunter’s heart begins to sink as he realizes the futility of any such attempt.

Stone sheep position themselves with maximum visibility to detect a predators’ approach from great distance, complete with escape routes up and over mountains and the wind in their favor. The best and most promising route always requires a great deal of the hunter’s physical aptitude as well as time. Should the hunter have the ability and even the heart to trek his way onward, he often finds he does not have the time, as the entire process has pushed him right up against dusk. And as the hunter mounts his horse and begins the procession home, he cannot take solace in the thought of returning first thing in the morning, because it is rare for Stone sheep to hold patterns or to stay where yesterday found them. And so the hunter returns to his shack to dry his clothes and hope tomorrow is better than the day before.

On our third day, we finally spotted a legal ram, but we waited the afternoon in ambush and nothing came of it. On two other occasions, we found sheep that were impossible to reach or not large enough to hunt. We took several excursions, all of which felt like blind stabs into sheep country. On one occasion we had a shot at a full curl sheep, but from a distance that did not allow us to age it. Our hunting guide was the type of hunter who loved hunting for its communion with the outdoors and not for the blood lust that drove him to hunger for the kill. This greatly enabled his patience, but ultimately made him indifferent to the progress of each day: namely, whether or not we killed a sheep.

Most hunters feed on the misery of the hunt. We prize our trophies not for trophy’s sake alone, but for the agony endured to win it. The price one pays to pull the trigger is part of the allure. Each species taken represents a victory over weather, timing, fatigue, expense and self-pity. And yet, to transcend the misery the hunter needs the heart-pounding lust for blood that rises at the closeness of the hunted – at the prospect of the kill. It was this hope that could not survive at Scoop Lake.

Our circumstance was unique. We were not trained or experienced sheep hunters. Our hunting guide lacked intensity, as well as knowledge of our particular hunting camp and its surrounding land. And yet, all these variables do not excuse how few sheep – only one legal sheep – we saw while on this trip. When reunited with Tom and his son, we learned they too felt disappointed at the surprising absence of game and were frustrated at the process. The books that spoke of sixty-seven rams now read as a history of a land no longer meeting the quota its reputation created. Frustration had replaced our fear, and the misery that met us did not tuck us in cozily at night with warm thoughts of home, but rather drove us mad.

As Dad and I sat afterward over coffee in Seattle, I knew that as with all miserable trips, I would revere the misery over time. Weeks would separate me from the reality of the cold rain and the moldy sandwiches. I would remember the smell of my horse, the warmth of a hot chocolate mug in my hand, the sweet taste of mountain lake water and the sound of the storms on our tin roof. I would always adore the time with Dad—laughter turning to tears in the suffering of it. And as always, I will sign up for the next adventure. But in the hunt there is always the hunger, and no hunter should endure misery only to remain sheepless in Seattle.