My nine-year-old daughter, Camden, hates to make mistakes. She wants to tear out the paper and begin anew as soon as there’s a blemish on the page. She is harder on herself than I could ever be, often inflicting her own punishment and dwelling in her disappointment. Yesterday she forgot her school lunch in her Dad’s truck, so during the lunch hour she decided to suffer the consequence and go hungry. Her friends convinced her she needed to eat something, so she bought a breadstick from the cafeteria. As in, a single breadstick. That was all she would allow herself after her error.

She has always been this way. It sounds like the cruel result of an overbearing parent, but I promise you that’s not the case. It is simply who she is. In my defense, look no farther than Ellie. We parent Ellie the exact same way, and she does NOT suffer from this issue. She has plenty of her own shortcomings, none of which affect her sleep. Or her appetite. If Ellie had discovered a missing lunch, she would have shrugged her shoulders, sauntered up to the lunch lady and declared: “One of each, please!”

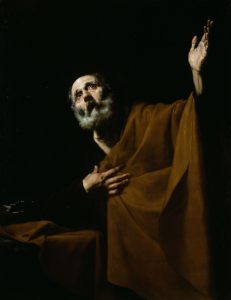

Last week I came across (and fell in love with) a painting at The Art Institute of Chicago. It was an oil painting by Jusepe de Ribera called Penitent Saint Peter. It depicts the disciple praying, presumably after his denial of Christ. One hand is stretched toward heaven, the other is pressed to his chest. His face is earnest and remorseful, but he is bathed in light.

I never realized how similar Peter’s story was to that of his fellow disciple, Judas, until Lisa-Jo Baker pointed it out in her book We Saved You A Seat. Both Peter and Judas were Jesus’ followers and friends, both betrayed him, and afterward both felt intense regret and wept bitterly. Where they differ, she noted, is how they handled their failure.

Sadly, Judas committed suicide. Whereas, the next time we hear about Peter he is the only one of the disciples who, after hearing about Jesus being raised from the dead, took off running toward the tomb.

Not away from, but toward.

Then later while fishing, he saw Jesus standing on the shore. Realizing it was Him, Peter plunged into the sea toward Jesus while the others remained in the boat. Baker wrote:

“…the more I study, the more convinced I am that each of their unique plot twists hinge on whether or not they believed Jesus could and would forgive them… Judas was crushed by the weight of his own guilt, and it killed him. But Peter, oh Peter. He went running and splashing, guilt and all, to Jesus.”

That’s what I see when I look at Ribera’s painting. Or similar ones by Caravaggio. In the contrast of light and dark, in the weathered faces and worn out robes, I see both the human— trembling, frail, dirty, limited— and the spirit. The former submitting, sin and all, however clumsily, to the latter.

It breaks my heart when I sit with a crying, disappointed Camden. The sight of her quivering chin and watery eyes is a knife to my heart. What I desperately want her to learn is that the best place for her after a fall is not the shadows, but the light. I want her to insist on hurdling the voice of condemnation and sprinting for God’s presence.

After Peter showed up sopping wet on the shore before Jesus, you know what he found? A charcoal fire, fresh fish on the grill, and bread. Jesus had made him breakfast.

Camden, baby, next time you forget your lunch, be it tomorrow or thirty years from now, don’t let that be the end of you. Just come home. If I’m around, I’ll make you breakfast. If I’m not, I know your Father will.

Love this, Steph.