In my last post about quitting, I wrote “When we refuse to be talked off our rock, He waits until we’re ready.” This expression— “talked off our rock”— is personal. It comes from my trip with the National Outdoor Leadership School which I mentioned in the same post.

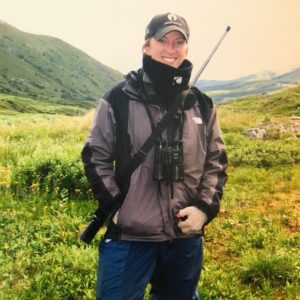

I hesitate to share the story at all. I recognize that there are harder circumstances than the one I experienced. I’m even embarrassed to share it with my husband because he endures misery so well, and occasionally climbs mountains for fun. Most recently he climbed Mt. Rainier with his sister and my brother, both of whom are the types to run marathons with little effort and with all their toenails intact in the end.

But I remind myself it isn’t about how difficult the circumstance, but about whatever circumstance it is that brings you, the individual, to the end of yourself. And so, I choose to share it.

NOLS is similar to Outward Bound, but I believe more technical and arduous. The U.S. Naval Academy sends trainees to NOLS. You can see a quick video on that here: USNA to NOLS .

Everything you need goes in a pack on your back. You share cooking and camping responsibilities with a small group of four or five. You learn compass and map reading, along with first aid. On a typical day, you wake up at 5:30 A.M. and cook breakfast on a camp stove. Then you clean the pan with snow or water from the nearest river, and break down camp. You practice “Leave No Trace” ethics, packing out every article of trash and returning the campsite to the way it was before you arrived. Once packed up, you set out in small groups for the day’s hike or activity, keeping to your TCP, or time control plan. You eat leftovers for lunch during a short break, and then move out again. Once you reach your “X”, you set up camp, cook dinner, clean pots, write the next day’s TCP, and do it all again. And as the group faces the challenges, responsibilities, and exhaustion together, leadership is also taught.

Before I went, my brother Trey gave me a letter. It changed my outlook and experience. I am convinced that had I not had his NOLS Letter, I would’ve entirely missed the point.

There are so many stories to share from NOLS, and I may tell more of them over time. But if I had to pick just one, it’s this.

The Boulder Field

This is it. This is where I quit, I thought.

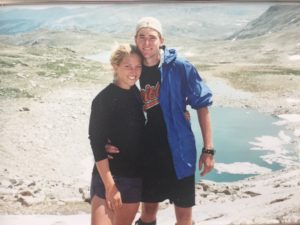

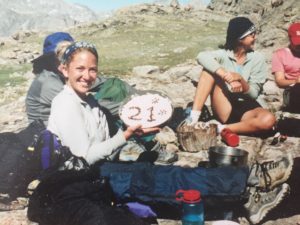

My brother, a NOLS grad several times over, had warned me that I would hit my wall. That I would meet myself. And this was it, the day before my twenty-first birthday in the Wind River Range of Wyoming, as the wind picked up and thunder rolled into a cold drizzle against my face.

I was standing on a rock just large enough for me and my pack, looking at the backs of my small group moving away from me and farther apart from one another. No one was within earshot, and even if they had been, the wind would have carried my voice away with it. No, I was alone, and I was alone in that moment whether surrounded by tent mates or not.

If I just sit here, my instructor will have to come back for me, I thought. This is where I will be, because I cannot go any farther. And she will realize I have stopped moving, and she will come back for me.

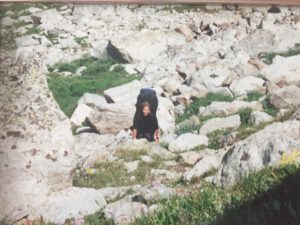

I was a third of the way through the boulder field that seemed never to end.

Earlier we had gazed down and out over it from the top of the pass, and our hearts had broken. Our fifth day on the course, this was the most difficult boulder field yet, and unexpected. Our instructor had misread our location three times, and three times we had reached the summit of a pass only to learn that we were not where we thought we were and would need to keep moving. With bodies aching, spirits sinking, we had pushed ourselves past the lines we had drawn for ourselves, working our way up steep elevation gains to finally reach our “X.”

“It’s just up here at the top of this ridge,” she had said. And we had fought to hit it. But studying her face at the top, I quickly realized we were still lost. I searched her expression, knowing in my gut we wouldn’t set up camp there on that ridge. I looked out over the boulder drainage, the largest one I’d seen, and told myself there was no way that she would ask us to go down that way. Not after everything we’d been through. Desperately I had watched her, waiting.

“We’re not where we’re supposed to be. We need to push through this boulder field. We’ll make camp down in that valley on the other side. We’ll find the rest of the group in the morning,” she said.

No one spoke. Usually at NOLS, tent mates talk while they hike. They chat, complain, encourage, tell jokes and tell stories. But NOLS also has those silent moments, when the circumstances, or the view, or the shared gravity of conquering or being conquered claims your collective breath like a vacuum. And nothing is spoken or needs to be.

The instructor then started off, moving at a quick pace, navigating up and over and around boulders ranging in size from half a foot to eight feet in diameter. And we all set out behind her, growing farther apart from one another as each and every rock took uneven amounts of time to scale.

In some places, the rock was loose and gave beneath your foot with your weight. I watched as Jon, the strongest and most burly of us, scraped up his leg as it disappeared inside a crumbling bed of rock. I remember the smell of heated stone from the friction as it gave way, the dust billowing out in a cloud around his waist, and the look of fear that gripped his face.

The sixty-pound pack made it difficult to move on small and large rocks. At that moment, I had just shimmied around one boulder and stepped onto another one, only to find a four-foot gap separating me from the next boulder. I was on an island, and I was done.

What will she say when she gets to me? I asked myself.

I assessed my surroundings. I am on an island of rock, in the center of a boulder field, on the side of a ridge, with a storm blowing in and the sun going down.

The rain was picking up, each drop heavy and deliberate, slapping my skin and coating my eyelashes. A helicopter won’t pick me up off of this rock, and even if it could, I’m not injured. The pack horse won’t pick me up off of this rock, and even if it could, re-ration isn’t at this location and it isn’t for three days. She will know this, and she will talk me off this rock. If I refuse, she will continue to talk, and offer me an arm, but either way, she has to talk me off this rock.

And then it came, the realization: I can make my instructor come back to talk me off this rock, or I can talk myself off this rock. Either way, I have to walk off this rock. Quitting the way I wanted wasn’t really an option. There was only taking another step.

And that was my moment— the moment when I took ownership of my story. I knew I didn’t want my story to be the one where my instructor had to come back for me. But the story I wanted to write couldn’t live alongside my feelings, so as I watched, my storyteller put a chokehold on how I felt. I was no longer quitting, I was taking another step.

It took minutes. I talked to myself a lot before I made a move, and I didn’t shut up. I don’t remember what all I said, I only know that eventually I took that next step, and the next one, and the next one, until I was to the end of that boulder field.

I watched Jon ahead of me when he reached the end himself, watched him drop his pack, hit his knees, and start crying. And then it was my turn to step off the last rock into the valley beyond it.

That night we made camp, and briskly ate, and went to bed. Around midnight our instructor woke us up and asked us to assume “lightning position” until the thunderstorm above us passed. It was torturous to get up and out of our sleeping bags. We huddled up within our tent, balanced on our beat and tender toes, hugging our knees, listening to the thunder shake overhead and rip at the sides of our shelter. And we woke again at 5:30 A.M. to another day of pushing hard. We were not done.

But for me, I was no longer the same person. At the end of that day I knew— not hoped, but knew— that I would finish the remaining twenty-three days of the course. I had acquired a skill— an ability to talk myself— that fortified me the rest of that trip, and the rest of my life. It got me through a marathon and law school and the bar exam, and a career as a criminal prosecutor frequently in trial. It got me through three childbirths and the continued sacrifice that came with parenting. And it got me through a thousand small, everyday moments when taking that next step meant talking myself off the spot I currently occupied.

At the end of my NOLS course, when small groups hike for several days without instructors, I was selected to be our group’s leader. I tried to lead from behind, to solicit input and foster a spirit of equality and teamwork. But whatever leadership role I practiced, be it designated leader or active follower or peer leader, none has had a greater influence on my life than the self leadership I learned on that boulder field. To act as my own instructor, my own advocate, my own story teller.

Nine strangers began that NOLS course together, and eight finished, one girl quitting within that first week. I remember trying to talk to her, to talk her off her rock. But every mosquito and every blister seemed to drive her more deeply into her own misery. I remember watching her leave on a pack horse, the lazy rocking back and forth of that horse’s backside with her on it, as they made their awkwardly slow exit toward headquarters. I remember feeling embarrassed for her, as she so publicly admitted defeat. But more importantly, I was sad for her story.

She, like all of us, had the power to tell it the way she wanted. I wanted her to write about the part where we reached the top of the Continental Divide, dropped our packs in victory and felt the glamorous relief of wind hitting our sweaty backs where the packs had been. I wanted her to write about how we found a cairn there at the top with a thermos buried inside filled with notes from hikers who had come that way, and how we read so many and added ones ourselves and sang together there. I wanted her to write about the time the guys intentionally shot the bear spray inside the tent to see what it was like, and then came tumbling out like bees from a hive crying and yelling, and how hours later when all recovered how we laughed and laughed and laughed about it. But she wasn’t there for that. In her great face-off, it was her storyteller that drew its final breath.

For me, NOLS is about the story you tell, and the larger one that is written when each individual’s different story of endurance and self-sacrifice comes together to create an entirely new, unique, and incredibly powerful experience. Each and every course that goes out and comes back writes their own, and each is filled with tears and laughter and accomplishment and growth. For me nothing has been the same since NOLS, and I’m forever grateful for that boulder field where I met myself, where I gave voice to my feelings and watched them fall lifeless from the grips of an adventure writer who stepped over them and off that rock, and never looked back.

My brother has also written about NOLS. Here is his piece: Star Gazing from the Gutter.